We visit quite a few stately homes where very rich humans lived, so as a direct contrast we decided to visit a workhouse, where some of the poorest humans used to live.

Very poor humans used to be known as ‘paupers’. There have always been humans that find it difficult to support themselves, some ending up homeless. Workhouses date back to the 17th Century. Southwell was built in 1824. Following the introduction of the New Poor Law, poor humans that applied for relief were supposed to only be offered the option of the workhouse (though in practice many were also helped outside the workhouse).

Inhabitants of the workhouse entered of their own free will and were free to leave but if they did so they had to take their whole family with them. While in the workhouse humans had to work all day on various tasks. Some of them would be working on the vegetable plot growing food.

The idea of the workhouse system was that they had to be worse than being poor living outside, so harsh rules were applied. On entry families were split up, with children being separated from their parents. It must have been terrifying to have to go to such a place, but the alternative of no food and sleeping on the streets equally awful.

Before we started to look round I did have a tasty chocolate brownie, served on a plate listing categories of poor people that entered the workhouse.

When new arrivals entered the workhouse they had to give up any possession and clothes (which were often rags) which would be cleaned then stored away to be returned to them should they leave again. They then had to have bath.

After bathing they were issued with workhouse clothes. Below is an example of the sort of clothes given to a man. All inmates had the same clothes. Clothes were numbered so that they could be returned to the right person after being laundered.

At Southwell workhouse for a while the inhabitants had red shirts. It is thought that a reasonably priced amount of red fabric must have become available! The shoes issued to them were clogs, which must have been quite uncomfortable to those not used to wearing them.

I headed across the yard towards the laundry.

Women would have worked in the laundry.

There was also a bakery. Bread was the main diet of the workhouse dwellers. Men would have 12 slices of bread per day and women 10.5; those outside of the workhouse would also mostly eat bread.

The list of rules and regulations. Anyone not conforming could be sanctioned and have punishments such ‘no meat at dinner’ applied to them.

The walls of the workhouse were kept freshly painted. During the restoration of Southwell the National Trust found that there are about 30 layers of paint on the walls. Painting was one of the work activities assigned to the men, and they painted the walls often in order to keep the men occupied.

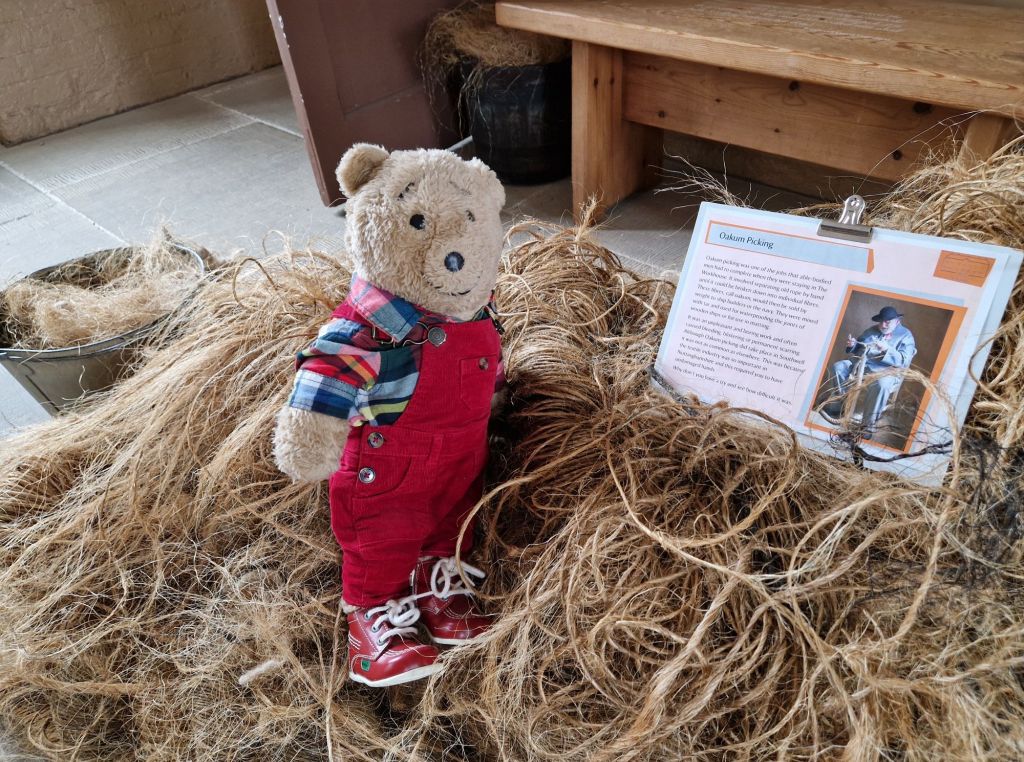

Another very boring repetitive job was picking oakum (old rope) which went on to be used for caulking ships. The work was very tedious and hard on the fingers.

Elderly, children and ill humans didn’t have to do any work, and there was an infirmary to look after very sick people. Here I am in the men’s exercise court, which has been restored by the National Trust. The walls are high and they wouldn’t have been able to see over them.

The outside latrines didn’t have a roof.

Workhouse inmates were given an hour for dinner after a morning of work. On three days a week boiled meat was served with peas and potatoes, soup on the other days. On a Saturday they were given suet pudding. The food was bland but was often better than many had experienced at home. After an afternoon of work, supper would be served, which would’ve been gruel, the same as breakfast.

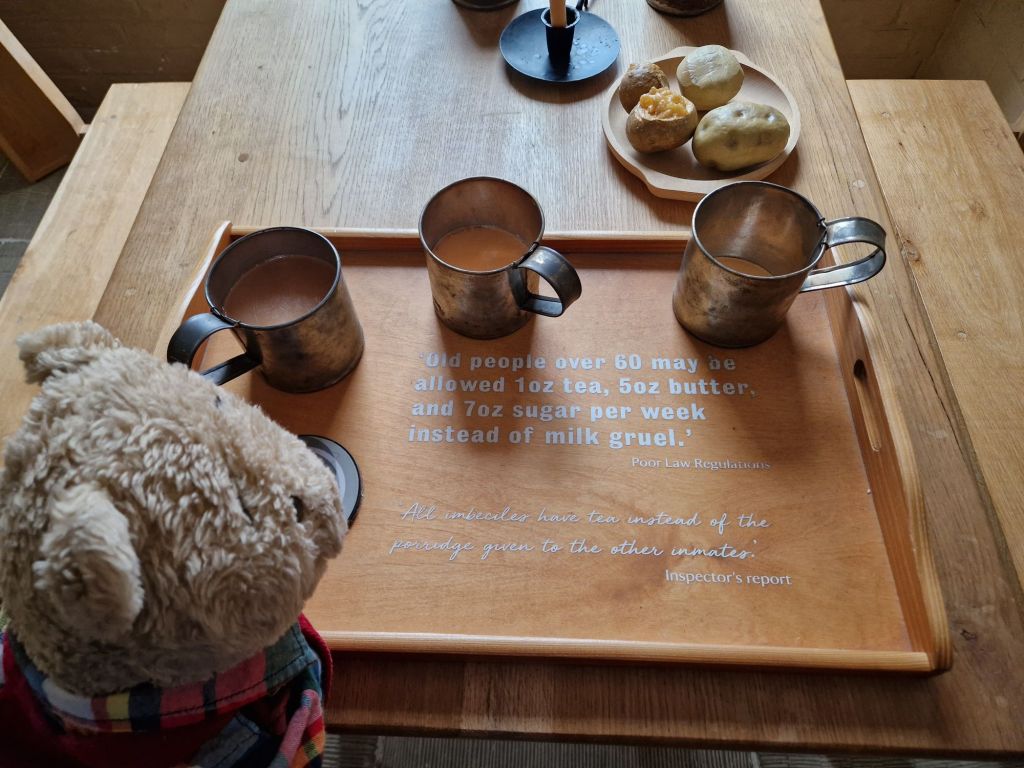

There were some different rules for ‘old’ people as seen on this tray.

This is the kitchen where food would have been prepared by the women inmates. The workhouse didn’t have many staff. A Master & Matron were in charge, but they were responsible to a board of guardians elected by local people.

The water that meat was cooked in was used to make soup.

The gruel that was served was very diluted porridge. My human makes porridge with 40g of oats and 400ml of milk.

A bell was used to announce daily timings as none of the inhabitants had watches.

A school teacher was employed at the workhouse, but the work was not paid well and had a low status in society. The female schoolmistress had to live in a the workhouse and had to supervise the children throughout the day as well as teaching them in the classroom. In 1870 the education act ensured schooling for everyone and in 1885 the workhouse school was abolished and the children were sent to local schools instead.

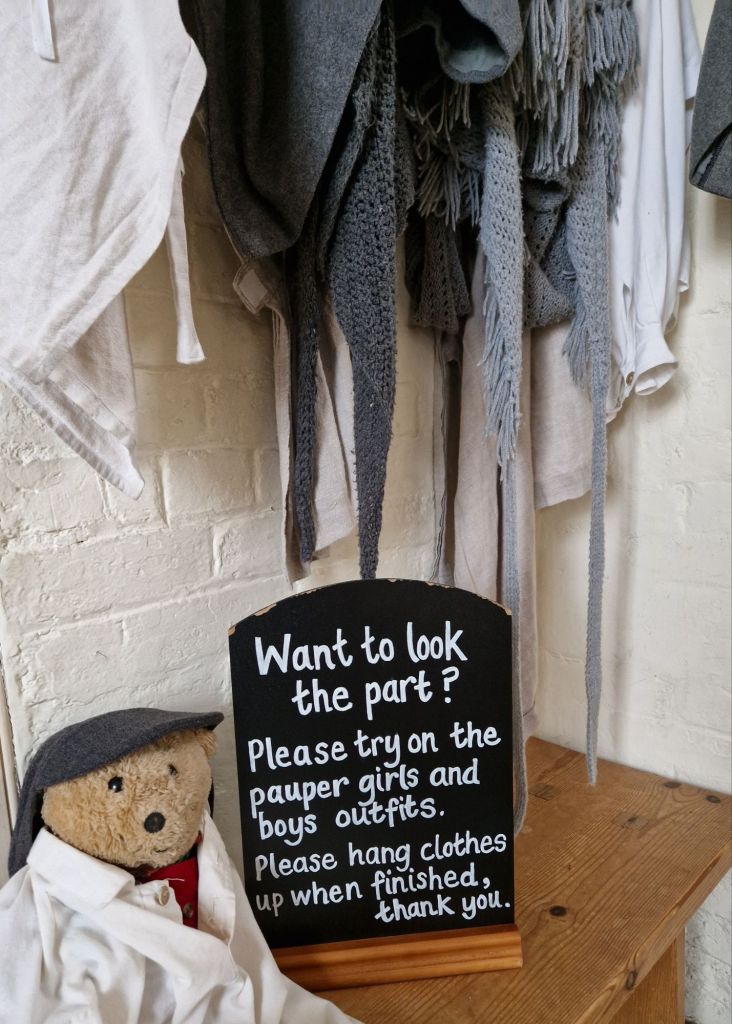

The National Trust often has some clothes for children to dress up in to ‘look the part’. They are always too big for me but I put some on anyway.

I felt a little bit sad as I posed in the classroom for this photo. The children that ended up in the workhouse had a miserable life, separated from their parents without even a teddy bear for comfort. There were however some toys and games available for them, such as hoops, often donated by the local community.

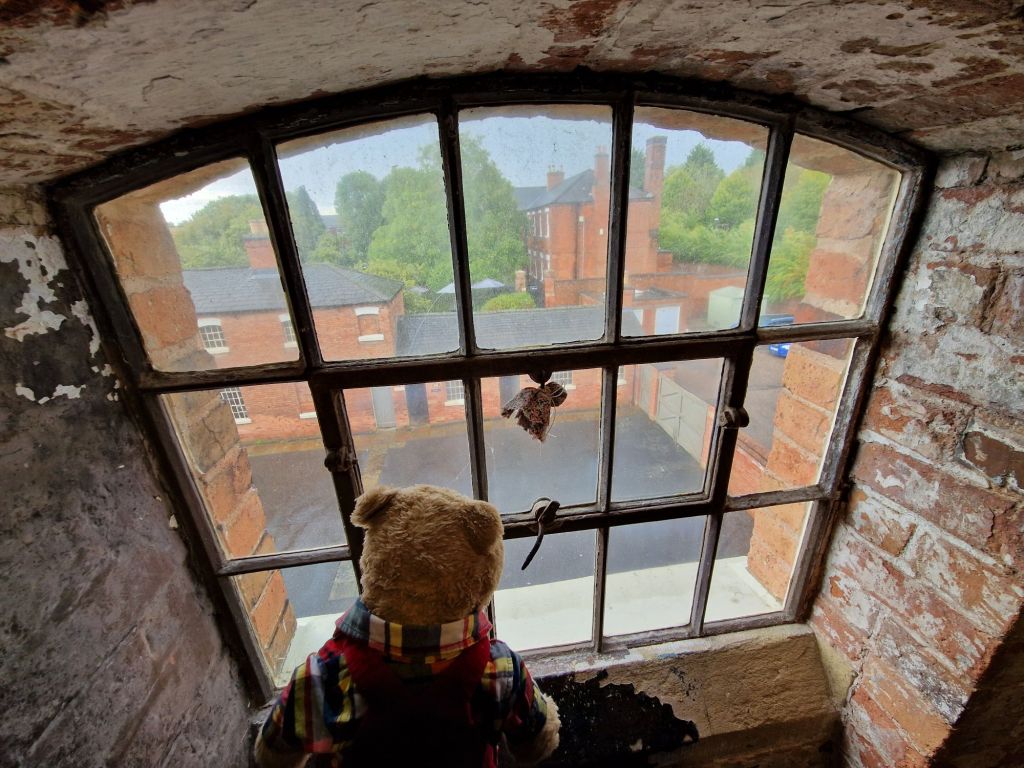

The stairs throughout the building looked very gloomy and depressing.

This room would have been the men’s dormitory, but would have had lots more beds when in use. Inmates had to get up at 6am (7am in winter) and then weren’t allowed to return to the bedroom until bedtime at 8pm.

The view out of the window shows the bakery and laundry opposite and infirmary in the distance.

I think this was the women’s dormitory.

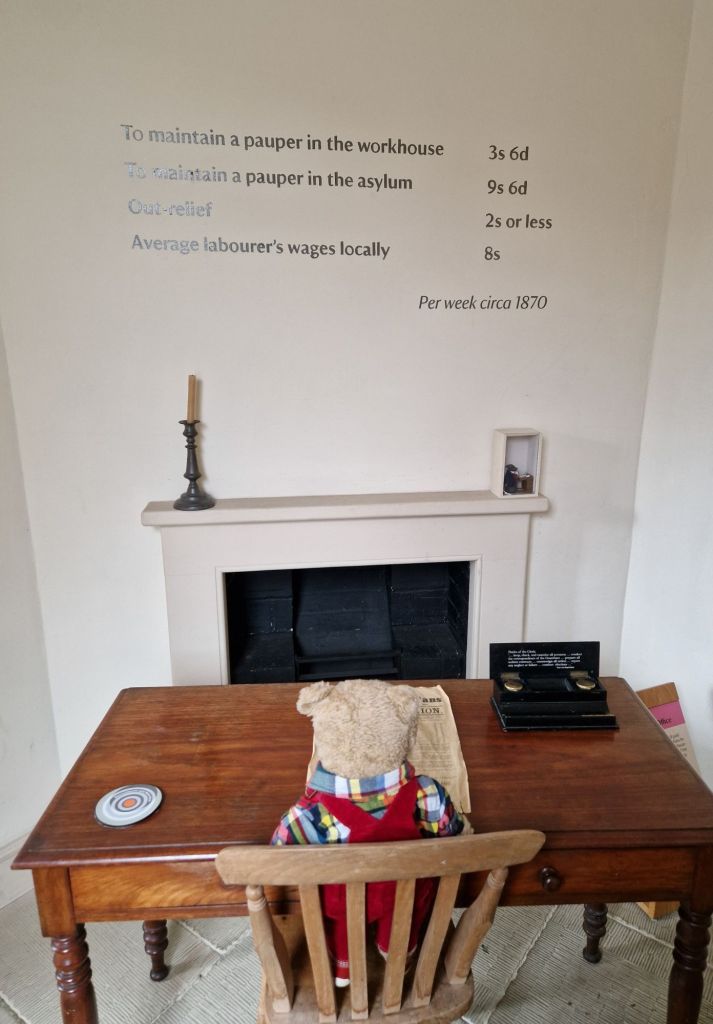

Another member of staff was the guardian’s clerk. This was a well paid position. The clerk wasn’t resident but had an office in the building. He kept records and took minutes of the meetings of the board of guardians.

The board of guardians met in this room.

In 1913 workhouses were renamed institutions, and due to the introduction of the state pension fewer elderly people ended up there. Southwell was renamed Greet House and went on to provide care for chronically sick humans. In the 1970’s some of the dormitories were used as ‘bed sitting rooms’ to house homeless families. The National Trust has preserved a room used that way…

It all looks very old fashioned but this was nearly 60 years ago…

The infirmary was next door to the workhouse, sick inmates were given healthcare there. A local doctor would visit once a week and could prescribe remedies, but back in 1836 antibiotics had not been invented. The doctor would sometimes prescribe an extra portion of meat or extra food of some sort to help ill patients. The Matron was responsible for nursing but would not have had any formal qualifications and would have been assisted by workhouse women.

The wall paper in the room shown below is of the type that would have been there in 1948 when former elderly residents were moved into the infirmary for their care. The main workhouse building continued to be used for staff accomodation and housed kitchens, and the west wing (pictured above) was used to house homeless families until 1977.

I decided against trying to dress as a nurse!

Before leaving I decided to buy a little mouse dressed as a nurse. One of the volunteers makes them and the donations go towards the cost of the upkeep of the workhouse buildings.

It was certainly a very interesting experience visiting the workhouse and it is good that he National Trust has preserved the building as a museum.

For more information about Southwell Workhouse see: https://www.nationaltrust.org.uk/visit/nottinghamshire-lincolnshire/the-workhouse-and-infirmary

Reference book:The Workhouse, Southwell. Author: National Trust ISBN 978-1-84359-008-8

Horace the Alresford Bear 14/9/2025

I really enjoyed reading about this experience Horace – as depressing as it must have been to live this way you have certainly educated me about this issue.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Horace, I have visited Southwell in the past and found the experience so sad. The whole place is well explained and the room that was last used in the 1970’s was heartbreaking

LikeLiked by 1 person

A very interesting trip Horace. Whilst doing our family tree I discovered several of my ancestors spent time and indeed died in the workhouse though some went in as they were the only kind of hospital available for the poor. It was an only a few years back I discovered that my two sons were born in Guildford Workhouse as it had been turned into the town hospital. I had no idea at the time. Most has been demolished for houses now but there were still some “cells” left were tramps slept if they broke rocks. It’s called The Spike if you’re ever up that way.

LikeLike